Sam Foose – Before Chip There was Sam

Foose. It’s a name as essential to the history of hot rodding as Parks, Petersen, Roth, Shelby, Barris, and dozens more. It’s the purpose of this column to chronicle these giants, the icons who created the hobby we enjoy today. Foose is just such a luminary. That would be Sam Foose. Huh? But what about Chip Foose, the design pioneer who overhauled the entire look of hot rods in the 1990s and 2000s? No, we’re talking about Sam – Chip’s father – who bent and shaped custom car metal long before Chip was old enough to sweep a shop floor.

Sam Foose was born in 1934 in southern California. When he was young, his father – also named Sam – took a job in the root-beer business up the coast in Santa Barbara. After a few years, the job went south and the family did too, back to LA. Well, not ALL of the family. Sam, age 14, decided to stay in Santa Barbara and take his chances going solo as a teenager.

To survive, Sam bunked in his girlfriend’s garage and turned wrenches to make ends meet; he’d learned basic metal and mechanical skills in junior high school shop. All this scrambling instilled in him a dogged, untiring work ethic, one that would power his life.

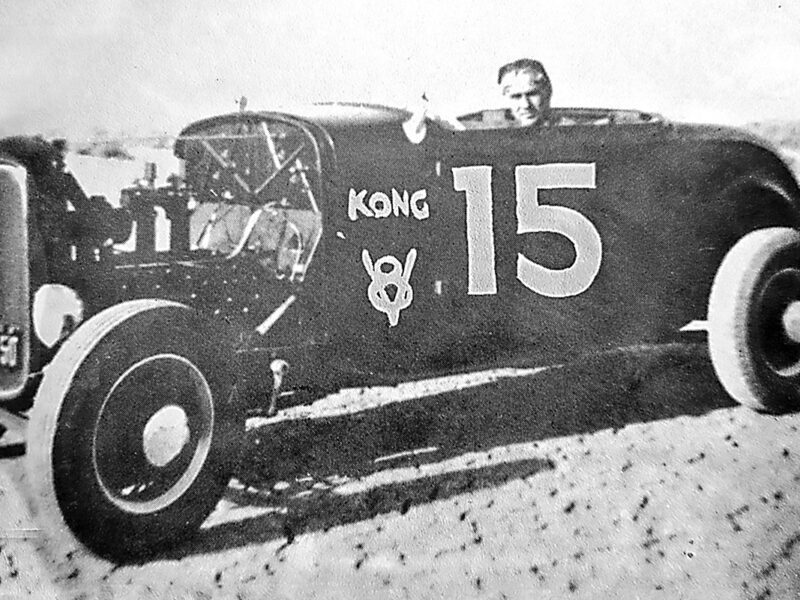

During high school Sam built his first hot rod, a customized ’42 Ford coupe, which was a portent of great cars to come. Later, the car won honors at the 1955 Los Angeles Autorama car show.

During high school Sam built his first hot rod, a customized ’42 Ford coupe, which was a portent of great cars to come. Later, the car won honors at the 1955 Los Angeles Autorama car show.

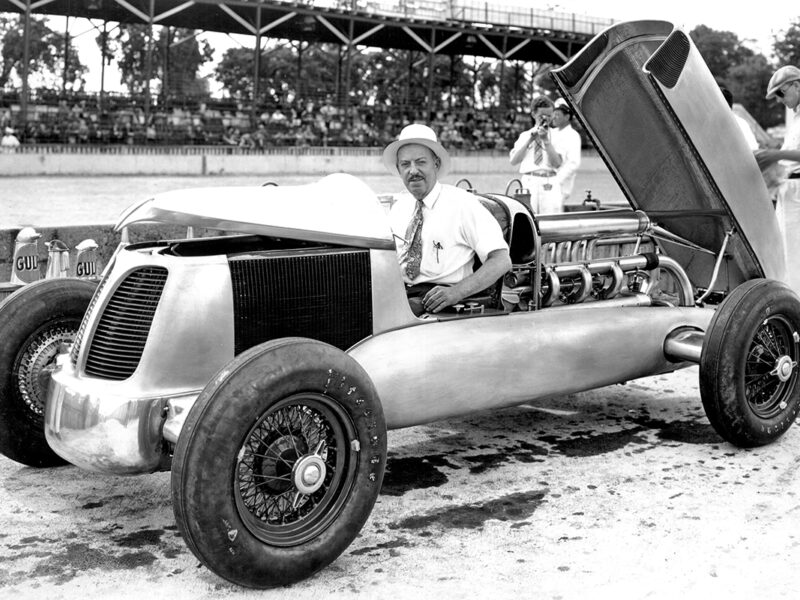

Sam’s journey toward car-crafting greatness was temporarily sidetracked by the Korean War. While in the service, he convinced his superiors he could repair all those broken Jeeps piling up, war casualties as it were. He set up a shop and did just that. Upon his return to the States, he continued to work on rods and customs. Then he got a break, a gig with model kit maker AMT.

At AMT, Sam worked alongside legendary customizer Gene Winfield, building full-size custom cars for later shrinkage down to 1:24-scale model kits. That job landed him a position with Minicars, where he put together “safety car” prototypes as part of a government-funded program that ultimately yielded air bags, crumple zones, and pedestrian impact standards. But off-hours Sam continued crafting cars; in 1970 he opened a shop of his own in Santa Barbara, called Project Designs.

By this time, Sam was married to Terry, a car-gal extraordinaire, and had four children at home (one named Chip). It’s here that Sam’s tireless commitment to his craft intervened with traditional family life, as 100-hour work weeks became common. Chip recalled the time his father stayed in the shop for four straight days and nights. This prompted Terry to bring dinner and the kids to the shop, so they could all eat together. This commitment gradually paid off when Foose’s creations began to grace the pages of hot rod magazines.

One of his most prominent builds was a ’49 Ford coupe, built in partnership with designer Harry Bradley and fabricator/customizer Donn Lowe, for owner Jack Barnard. It’s difficult to improve on the lines of a shoebox Ford coupe, but the stretched and smoothed Foose/Bradly creation was indeed stunning. The buff books agreed, providing extensive coverage, which enhanced Sam’s reputation.

Sam could pull off unconventional projects as well, none more so than his unique take on the Alfa Romeo Carabo coupe concept shown at the 1968 Paris Motor Show. Sam’s version began with a crashed ’72 DeTomaso Pantera, which came stock with a 351c.i. Ford V8 rumbling mid-ship behind the passengers. The car’s profile was dramatically angular. It looked sleek enough to fit inside mail slot. Sam eventually sold the car, but decades later Chip tracked it down and presented it to his dad – who hadn’t seen it in 40 years!

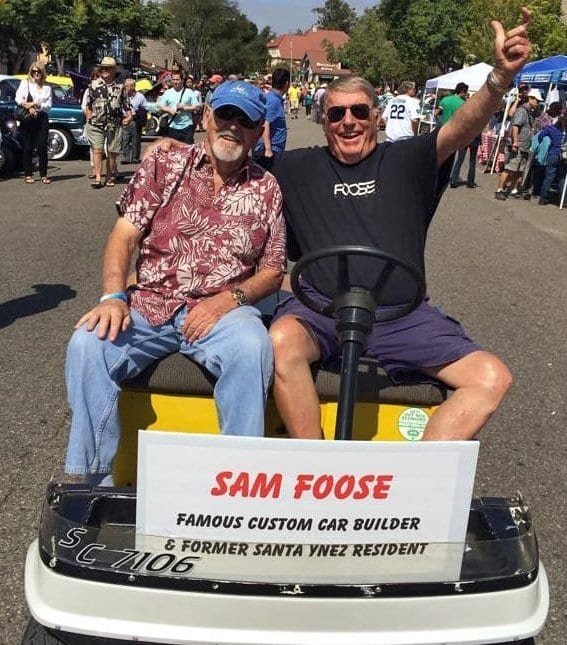

By the early ’90s Chip – schooled informally by his father and formally at Art Center College of Design – began his own career in automotive design. Naturally, the two would often team up on projects. Sam also made regular appearances on Chip’s successful television show, “Overhaulin’,” where he was quick to recite such maxims as, “you’re only as good as your customer allows you to be,” and, “less is more, but doing more with less is better.”

Sam Foose was also good friends with Goodguys founder Gary Meadors, who in the ’80s recruited Sam to update his ’32 Ford Tudor – the Goodguys logomobile – and later had him build a contemporary custom ’56 Continental Mark II with help from Denny Olson and Street Rods by Denny.

John Drummond, former Goodguys all-around talent and long-time veteran of the hot rod scene, was effusive about Sam’s talent and influence. “Sam Foose was one of a kind,” Drummond said. “Gregarious as well as cantankerous, he was always good for a belly laugh. His true genius was in his vision to move metal around and subtly change the proportions of classic American cars. While he wasn’t the first customizer to do this, he was at the forefront of the custom rod movement of the 1990s. In my opinion, Barnard’s ‘49 Ford was Sam’s Mona Lisa.”

Goodguys spoke with Chip recently about his father, who passed away in November of last year at age 83. “He was my mentor, my father, and my best friend,” Chip said. “And he was so talented. People don’t realize he was a gifted artist and was accepted into Art Center College Design – but turned it down. He said he would rather build cars than draw them.”

Goodguys spoke with Chip recently about his father, who passed away in November of last year at age 83. “He was my mentor, my father, and my best friend,” Chip said. “And he was so talented. People don’t realize he was a gifted artist and was accepted into Art Center College Design – but turned it down. He said he would rather build cars than draw them.”

“Despite all my success, I still feel like I’m trying to prove myself to him. And I’ll always feel he was better than me. I miss him greatly.”

We all do.