Ak Miller – A Hot Rodder’s Hot Rodder

Imagine if there was a movement to construct a hot rod version of Mt. Rushmore. A hot debate would surely follow on who is worthy of having their countenance chiseled in stone, say, in the hills overlooking the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Wally Parks would be one sure-fire candidate. Maybe Robert E. Petersen. Hard to ignore Ed Iskenderian or Vic Edelbrock Sr. But there would be universal agreement on one candidate – Ak Miller, whose racing accomplishments span success from the dry lakes to Baja, from Sicily to Bonneville.

No wonder Hot Rod magazine once tagged Ak as the “The Best Hot Rodder in the World.”

Miller was born Akton Moeller, in Denmark, in 1919. His family migrated to Whittier, California when he was a toddler. His childhood included a brief spell working at the Nixon family store – yes, that Nixon – where one of his tasks was fetching candy bars for the future president (more on this later).

Ak’s first taste of hot rodding was served up by his brothers, Zeke and Larry, who campaigned a four-cylinder Chevy drop top at the lakes in the mid-’30s. Miller spent considerable time behind the wheel of that roadster – but not roaring down Muroc. No, it came at the end of a tow chain.

“We were headed out to Muroc Dry Lake,” Miller told the American Hot Rod Foundation. “No trailer, no nothing. Just a chain. You know who was going to drive it? Me. I remember 100-and-some miles across a frozen desert. It was colder than hell.”

Yet opportunity soon knocked. When Zeke demurred driving, 14-year-old Ak Miller jumped behind the wheel. No problem. He blew through the timing trap at 94mph. The year was 1934. Miller’s love for speed was set.

A few years later he befriended one Wally Parks and together they helped form the Road Runners car club, one of the original seven clubs that formed the Southern California Timing Association. Miller would later serve as SCTA president.

As with many of our hot rod legends, World War II interrupted their racing career. Miller participated in the Battle of Bulge in 1944, but frostbite sent him back to a British hospital and the states.

After the war, the Miller-Parks collaboration continued apace. As part of an effort to clean up hot rodding’s “outlaw” image, Parks, with a PR push from Hot Rod magazine, established the National Hot Rod Association in 1951, with Miller one of the original founding members and NHRA VP.

In another historic milestone, Ak Miller, again with Parks and Petersen, spearheaded the first meet at Bonneville in 1949. The trio sweet-talked the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce into allowing racing on the salt flats.

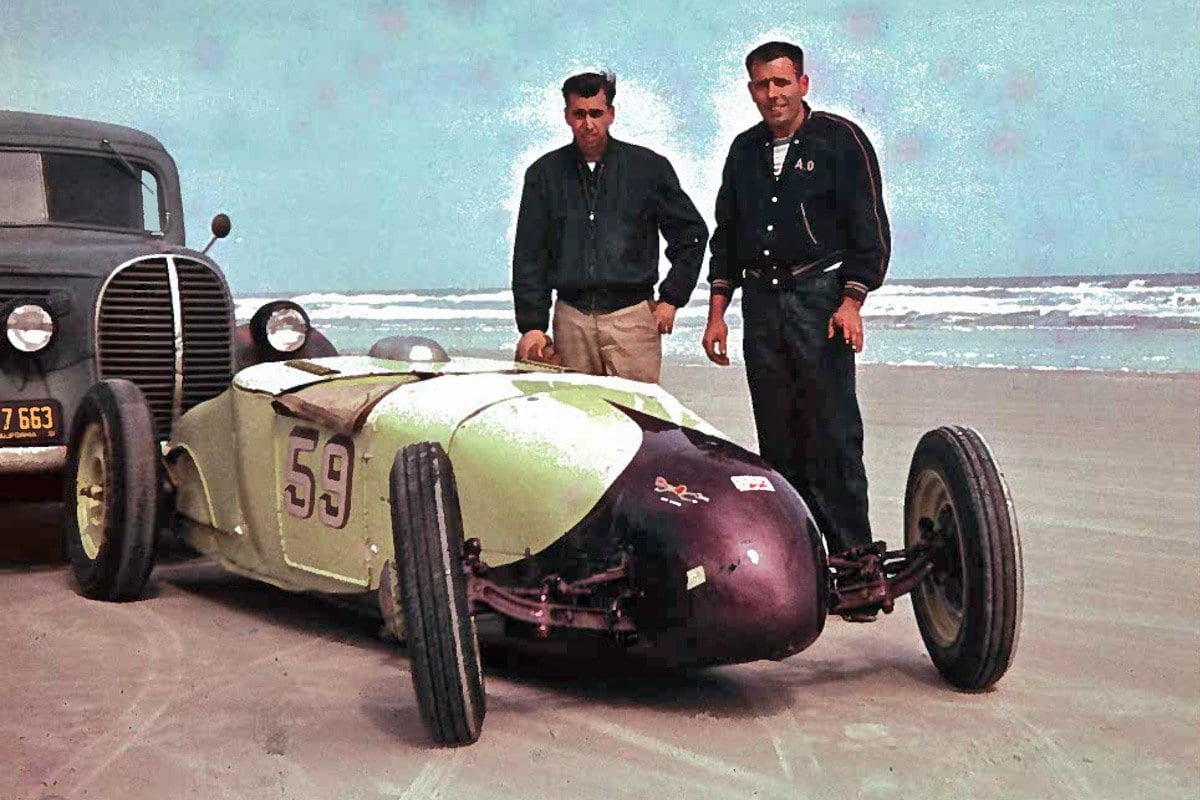

While all that politicking was important, at heart Miller was a racer. And few racers were as multi-dimensional and successful as Ak. At that first Bonneville meet he ran a ’27 T roadster built by Parks, who had improved its aerodynamics by grafting on a P-51 drop tank’s bullet-shaped nose and a belly pan that smoothed airflow under the car. It remains one of salt racing’s most iconic cars.

Miller also competed in the Pikes Peak Hill Climb, Baja 1000 off-road races, and events in Italy (the Mille Miglia) and Mexico. With Hot Rod magazine’s Ray Brock as his crewman, Miller won his class at Pikes Peak nine times and won his class in the Baja 1000 three consecutive years, 1967-1969, in a Ford Ranchero.

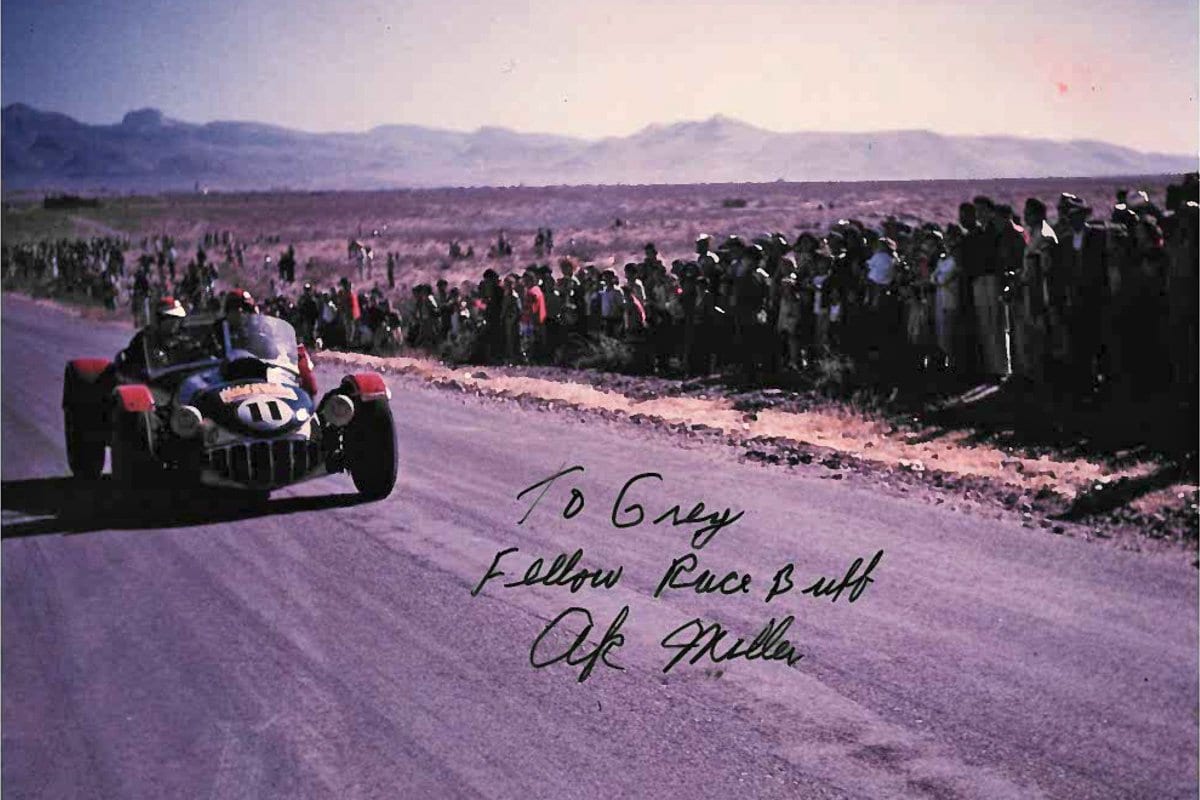

Perhaps Miller’s most significant and racing accomplishment – and unique car – came in 1953 in the La Carrera Panamericana. The route spanned the length of Mexico and was held to celebrate the completion of the Pan-American Highway in 1950. Miller built a specific machine – the Ak Miller Special, a.k.a. “El Caballo de Hierro” (“The Iron Horse”), an amalgamation of ’27 Model T Ford body, ’50 Ford chassis, and Olds engine. Los Angeles Times motorsports reporter Shav Glick reported that Ak’s fusion of components was dubbed the “Ensalada” – a salad of parts.

Glick also reported that Miller (again) had no trailer and no sponsor save for Hot Rod magazine. Miller drove the car from his home in Whittier to the start line in Juarez, Mexico (across from El Paso), raced over the 2,000-mile course for six days and drove back home.

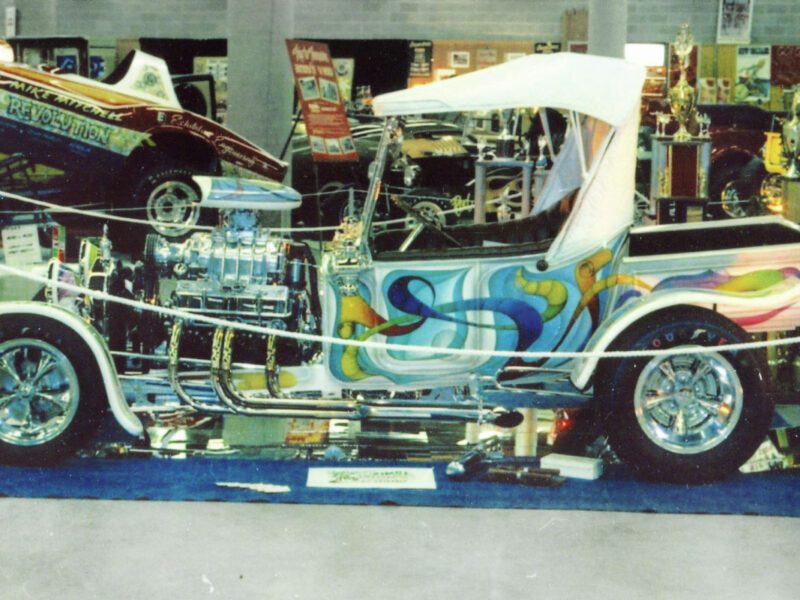

In addition to his racing exploits, Ak also worked for Ford as a performance consultant for a decade, touring the country with hot car displays and working closely with FoMoCo engineers.

Years later, Miller was invited to the Nixon White House with a group of racing personalities. His fellow racers were kidding Ak about the legitimacy of the candy bar story. When Nixon strolled into the room, he grasped Miller’s hand and said, “Ak, did you bring me a candy bar?”

Let’s have Wally Parks have the final word: “Ak was fascinated at producing combinations of his own, including his repowered vehicles, for street use, dry lakes, and Salt Flat speed trials. His innovative skills were an inspiration to all young hot rodders of that era.”

Ak Miller passed away in 2004 at age 84. That hillside in Utah awaits his sculpture.