Endurance Racing at Bonneville During Speed Trials

Images of the Endurance Racing at Bonneville during Speed Trials are elusive. Our photographic memories of Bonneville typically feature a pencil-shaped streamliner blurring across a limitless expanse of salt, guided by a thin black line that leads to infinity and beyond. Those record runs we all admire? All straight-line blasts.

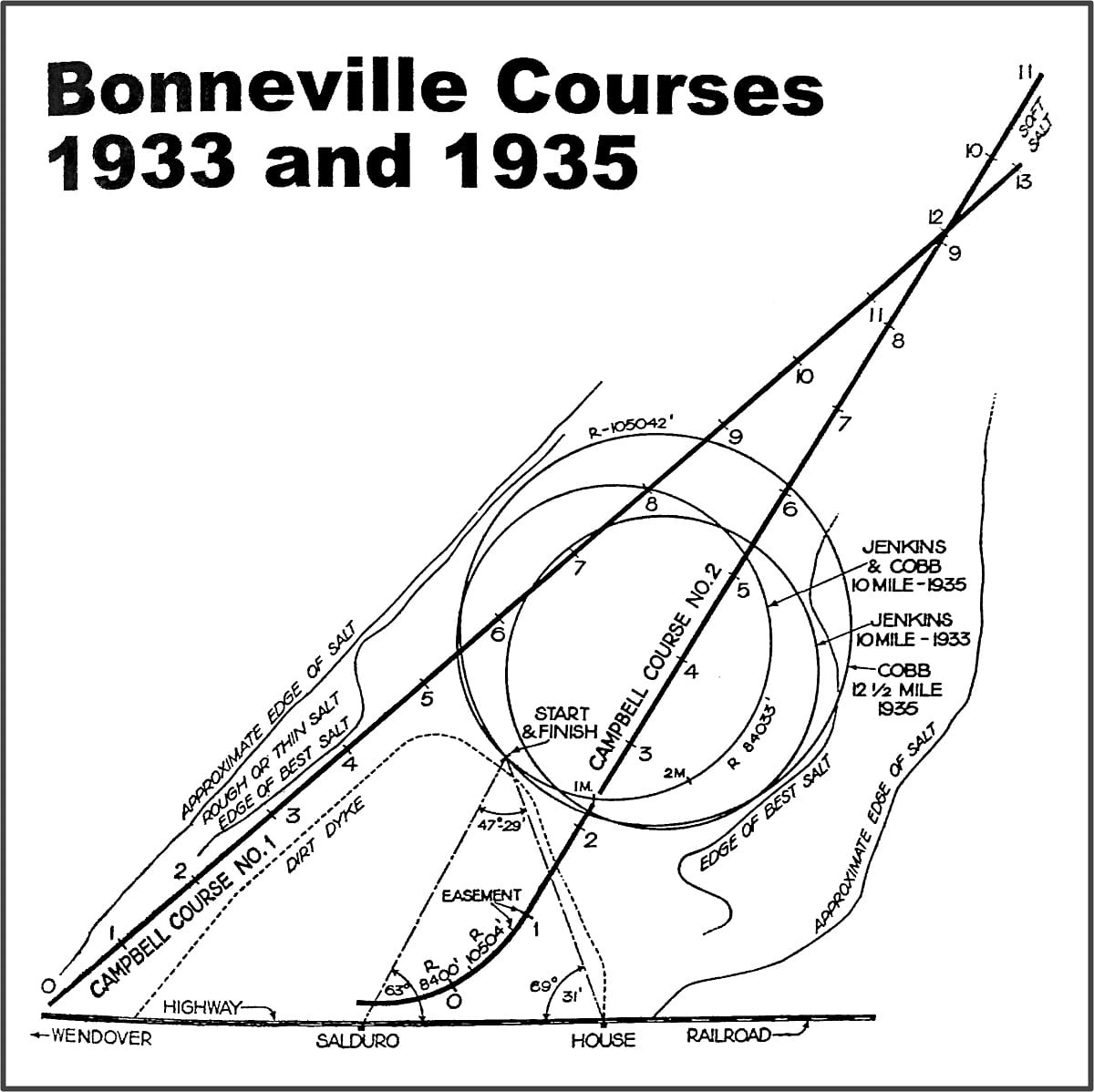

But in the early days of Bonneville the famous venue threw a curve at the racers. Beginning in the 1920s, racers held endurance speed runs held on a 10-mile diameter loop. Yes, before the Bonneville Speed Trials were a lab for arrow-straight velocity, it was a circle track.

It all began in the 1920s when David Abbott “Ab” Jenkins — a.k.a Utah’s Son of Speed — drove from New York to San Francisco in a Studebaker touring sedan, racing a locomotive, which held the record for cross-continent jaunts. Jenkins and his co-driver knocked 14 hours off the train standard: 86 hours and 20 minutes compared to the train’s 100 hours.

Duly inspired, in 1932 Jenkins believed a new 12-cylinder Pierce Arrow engine had record-setting potential. Pierce-Arrow agreed and sponsored an effort by Jenkins to set a 24-hour endurance speed record. That really big salt lake in Utah would be the track.

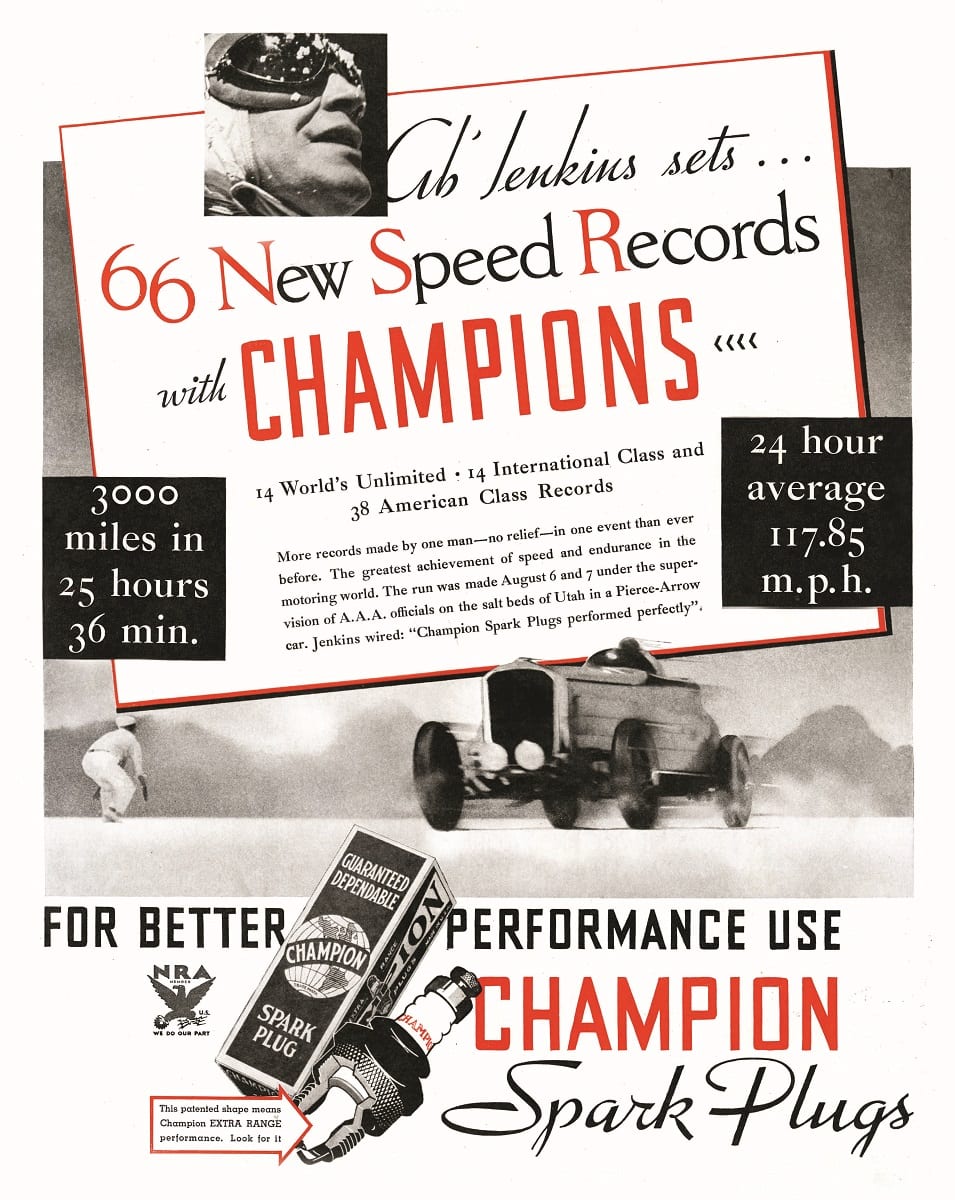

On September 18, 1932, he drove the V12 powered Pierce-Arrow roadster (sans running boards and fenders), an astonishing 2,710 miles at an average speed of 112 mph. The course was a 10-mile circular loop, with white cat-eye reflectors mounted on rods four feet above the salt surface every 100 feet for the entire ten miles. A year later, he bumped the record up to 117 mph. The record was so impressive, Pierce Arrow released a full-length movie, Flight of the Arrow, to celebrate the feat.

And Jenkins wasn’t done. In 1934 he upped the record to 127 mph for 24 hours, covering 3,053 miles. In his definitive book on the salt, “Bonneville – A Century of Speed,” motorsports historian David Fetherston explains what happened next:

“These Bonneville records would be the start of a long list of impressive 12, 24, and even 48-hour endurance records that Jenkins would set. Others came and set records for all kinds of speed and distance, but none ever challenged by sheer volume and audacity what Jenkins would accomplish even 70 years later. He was still racing as mayor of Salt Lake City, when he set 21 more records.”

The early records by Jenkins caught the attention of UK’ speed junkies Sir Malcolm Campbell, John Cobb and George Eyston, who had been racing across the sands of Daytona Beach. In the mid-1930s, Cobb too went to Bonneville and set endurance records of his own in a 24-liter Napier-Railton and narrowly improved on one of Jenkins’ records by only 53 yards.

Campbell, though, was mostly interested in straight line speeds, hoping to break the 300-mile mark. He did just that on September 5, 1935, driving his famed Blue Bird to 301 mph.

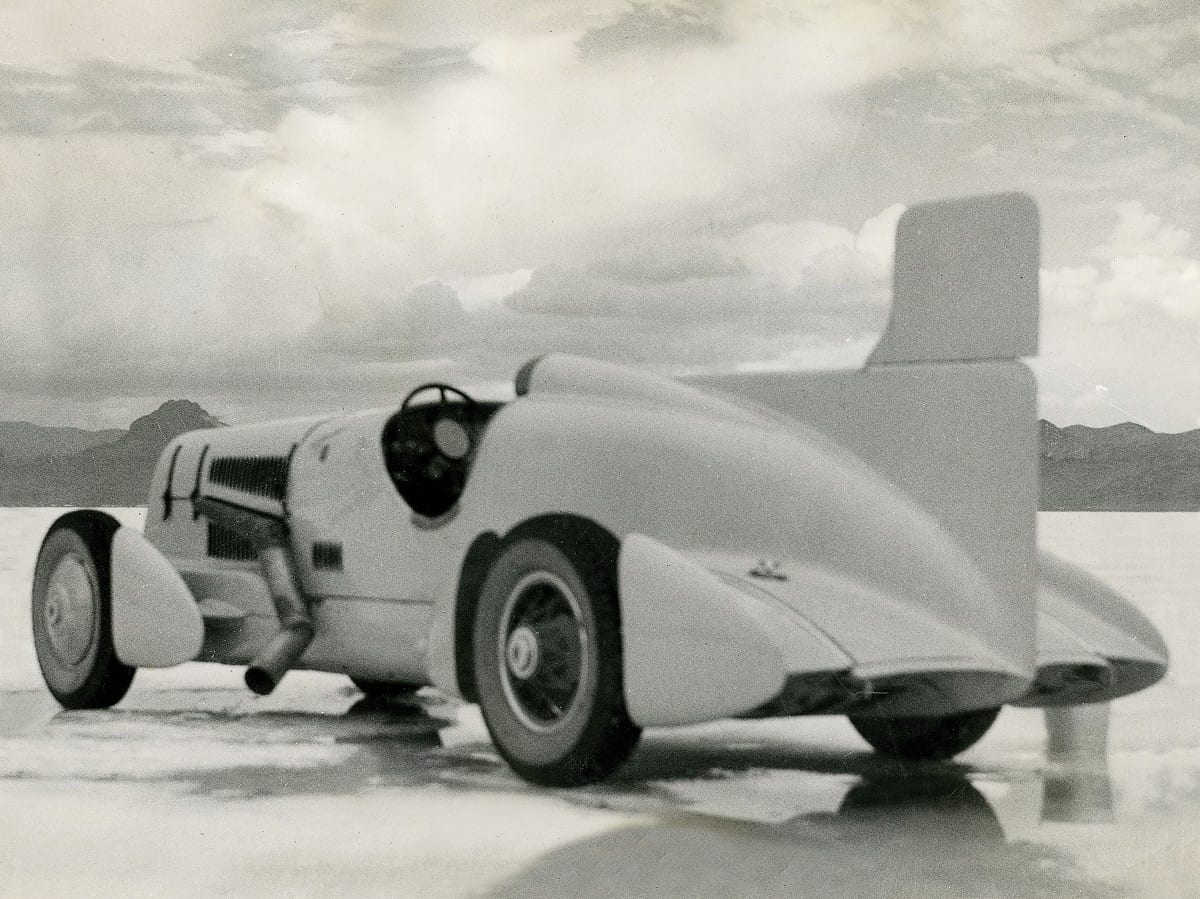

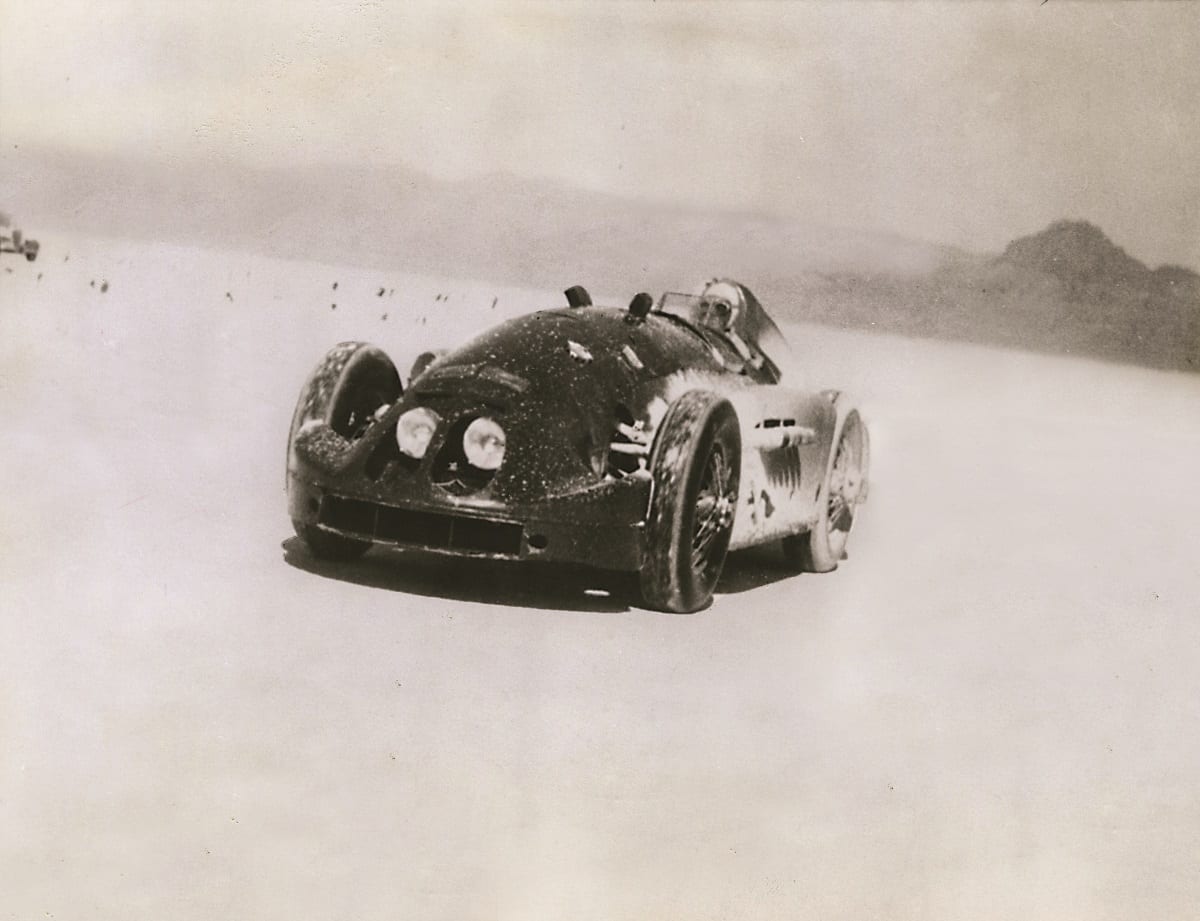

Meanwhile, fellow Brit Eyston was keen on overtaking Jenkins in the endurance record book. His sleek Speed of the Wind machine was propelled by a Rolls-Royce aircraft engine. In 1935, Eyston and co-drivers Tim Rose-Richards, Charles Brackenbury, and John Hindmarsh set endurance records for 100 and 200 kilometers, 1000 and 2000 miles, and upped the 24-hour record by 13 mph to a head-turning 150 mph.

Jenkins was determined to reclaim his status as endurance racing’s premier practitioner. When Pierce Arrow folded, Jenkins was recruited by Duesenberg to boost the brand’s performance image. Enter the “Mormon Meteors,” – a series of Duesenberg-powered machines aimed at topping Jenkins’ earlier records. Meteor I used a 400 hp supercharged Duesenberg engine; Meteor II ran a 650 hp engine. Both cars were designed and built by Augie Duesenberg, as was Mormon Meteor III.

In 1940, Jenkins’ son, Marvin, drove the Meteor III through a trial lap of 208 mph. In July, Jenkins took the wheel of the two-ton, 750 hp Mormon Meteor III, and 24 hours later, a new record had been set: 161 miles an hour average.

More mind-blowing records followed. Two hundred miles at 196 mph, 1,000 miles at 172 mph, and 3,000 miles at more than 165 mph. His land speed records stood nearly 50 years.

Jenkins continued to race the Meteor III until 1951, when minutes away from a new one-hour record, he lost control and damaged the car. He was 68 years old. Five years later he was back. He and Marvin drove a stock-model series 860 Pontiac around a salt circle at an average speed of 118.375 mph, eclipsing the old 24-hour mark of 109 mph and shattering all existing American unlimited and class C stock-car racing records.

Conversely, Campbell and others continued to press for additional straight-line speed records through the late 1930s. World War II intervened and salt fell silent — until southern California hot rodders started the modern-era Bonneville Speed Trials beginning in 1949. Endurance speed records, meanwhile, became mostly limited to manufacturers looking to boost their car’s reliability bona fides.

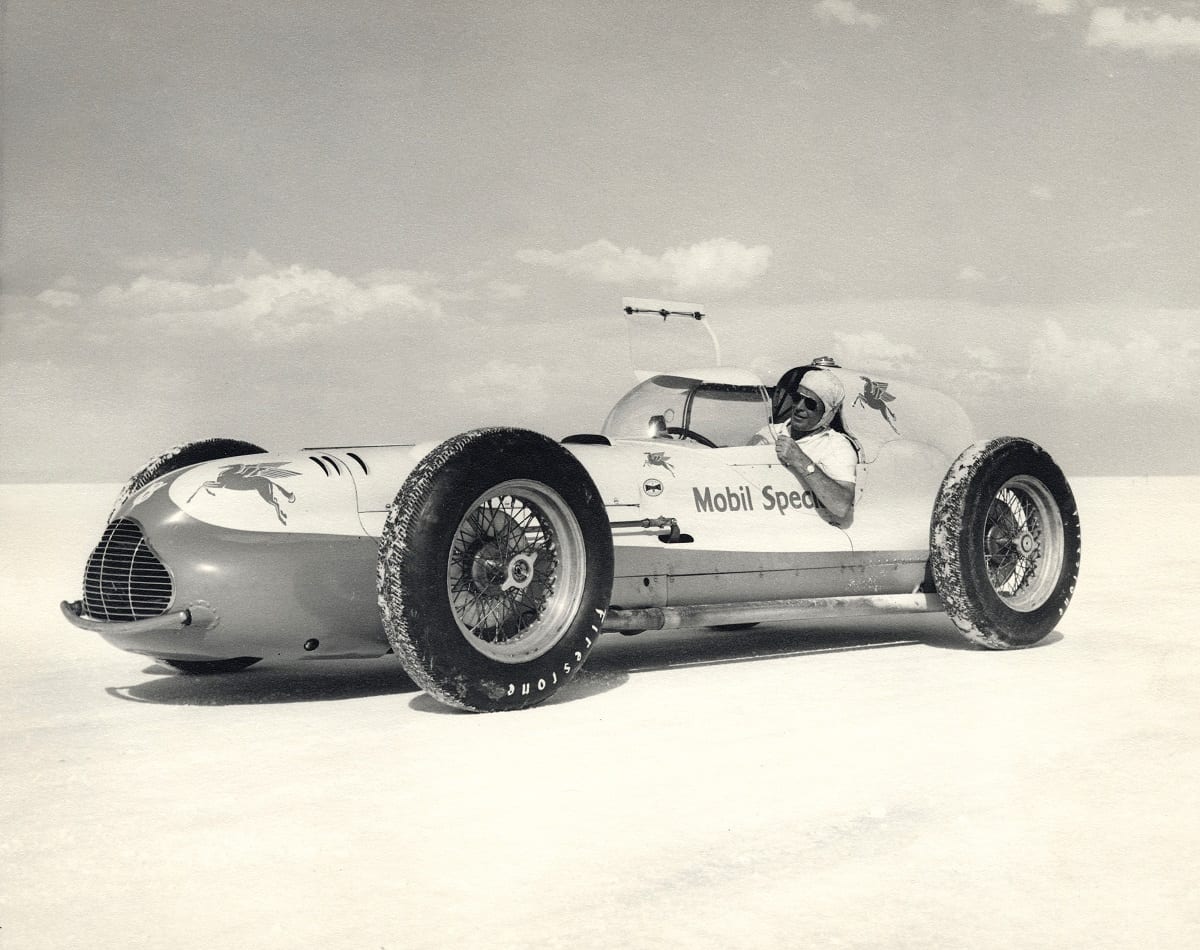

One exception, of course, was the irrepressible Mr. Jenkins and his son Marvin, who in 1947 drove the “Indy Novi Mobil Special” — a promotional effort by Mobil Oil. Runs were made in two directions on a loop. After two days, the Novi set an average speed of 179 mph for a D-class endurance record for 5-, 10-kilometer, and one-mile distances.

Over the next three decades, Bonneville Speed Trials focused primarily on straight line speed. One American hot rod icon who did just about everything was Mickey Thompson. Mickey, of course, ran all types of streamliners down the salt, but he also dabbled in special endurance speed attempts at Bonneville – not many remember that. In 1962, Thompson built a radical car for the Indy 500, the Harvey Aluminum/Harcraft Special. Teaming up with British chassis designer John Costlewhaite, The Harvey Special utilized a Buick V8 and independent-suspension. He recruited Dan Gurney to drive.

While a mere Speedway rookie in ’62, Gurney managed to qualify eighth; he was running in the top 10 when the transaxle failed. But Thompson — never one to waste a fast race car — had another idea: an endurance record attempt at Bonneville. Out went the Buick, in went a Chevy. Mickey replaced Gurney in the cockpit. In an impressive demonstration of salt flat circle racing, Thompson set 35 national and eight international speed records.

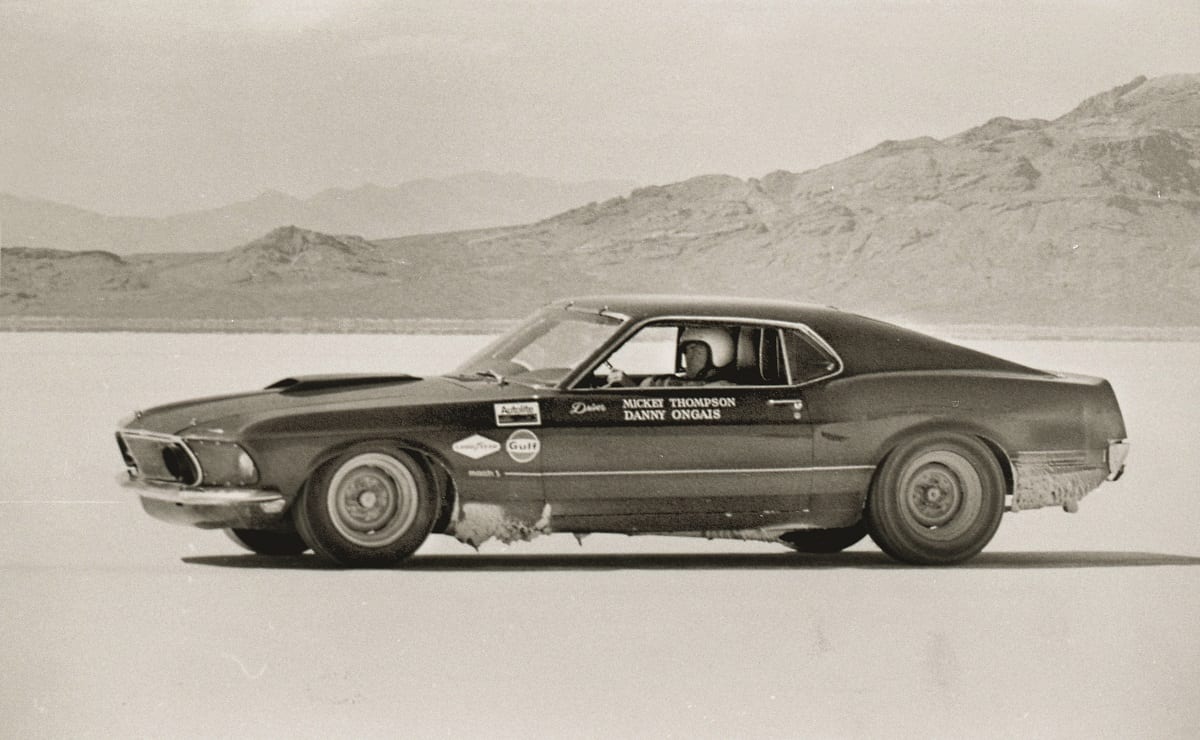

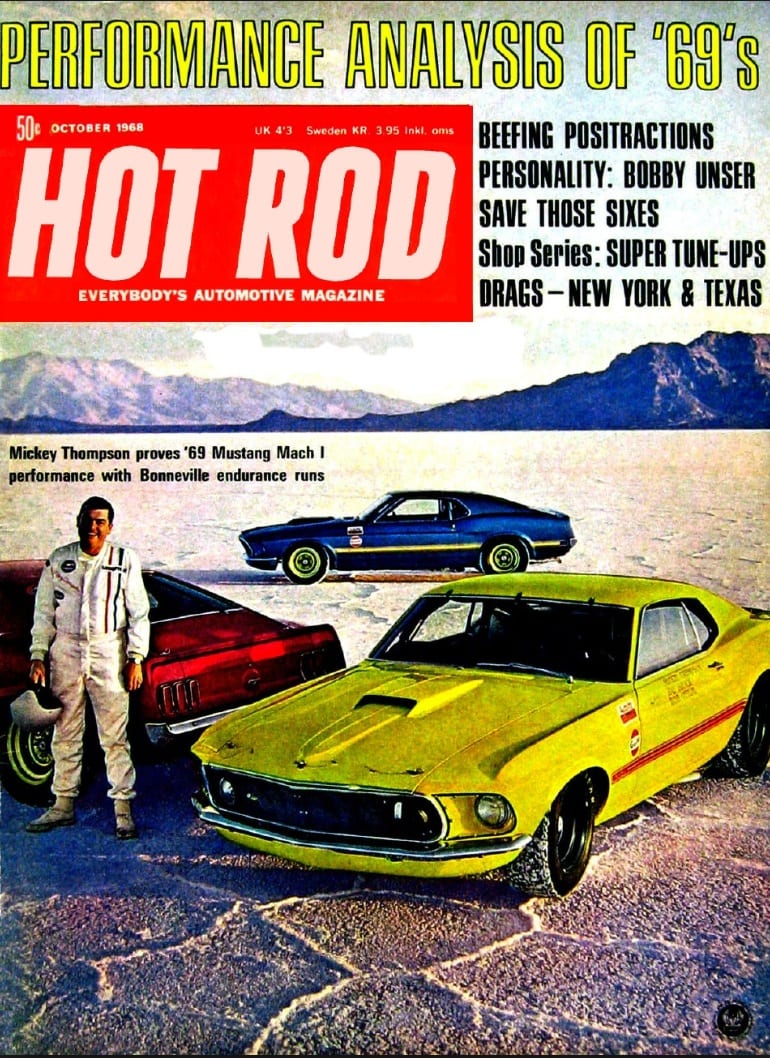

Perhaps channeling his inner Ab Jenkins, Thompson performed another Bonneville endurance trick in 1978, this time on behalf of Ford Motor Company. He launched the “Mustang Challenge Runs,” an endurance-record assault with three specially prepped Mach 1 Mustangs during the summer of 1968 (a half century ago). Both 302 and 427 engines were deployed. He shared driving duties with drag race (and later Indy Car) star Danny Ongais.

On a special oval loop carved into the salt by the Utah Highway Department, Mickey and Danny set more than 295 USAC-verified records in both the American Closed Car class and the American Closed Car Unlimited class. Perhaps most impressive, the 302-powered ‘Stang averaged 157 mph for 24 hours, traveling 3,788 miles. All three cars were featured on the cover of Hot Rod magazine.

These days, there are several paved test tracks that can host high-speed endurance runs, but the endurance records set at Bonneville are special, adding another bit of hot rod history to what is without question, the most famous salt-encrusted lake on the planet.

To learn more about Bonneville history, check out Bonneville-A Century of Speed, by David Fetherston